Goldman Sachs continua a randellare il governo formato da Movimento 5 Stelle e Lega. Non solo: la banca d’affari dopo aver criticato la manovra finanziaria dell’esecutivo Conte, poco incline all’austerità, ora si lancia in auspici politici: presto il governo giallo-verde collasserà a finalmente ci sarà o una maggioranza di centrosinistra o di centrodestra che esaudirà le attese della Commissione europea.

CHE COSA DICE GOLDMAN SACHS CONTRO IL GOVERNO M5S-LEGA

Ecco quello che dice la banca d’affari americana: “È improbabile che il Governo sopravviva fino alla metà del prossimo anno”, si legge nell’ultimo rapporto degli analisti di Goldman Sachs Più facile che venga “sostituito da un esecutivo internamente più coerente o di centrodestra o di centrosinistra, che segua una politica di bilancio meno aggressiva, incentrata o su tagli alle tasse (flat tax) o su un aumento dei trasferimenti (come il reddito di cittadinanza, ndr), ma non su entrambe le misure”. Un tale risultato, scrive ancora Goldman Sachs secondo l’Agi, “limiterebbe l’aumento del deficit e del debito pubblico rispetto al programma del governo attuale”.

LE PREVISIONI NEFASTE DI GS SUL GOVERNO CONTE

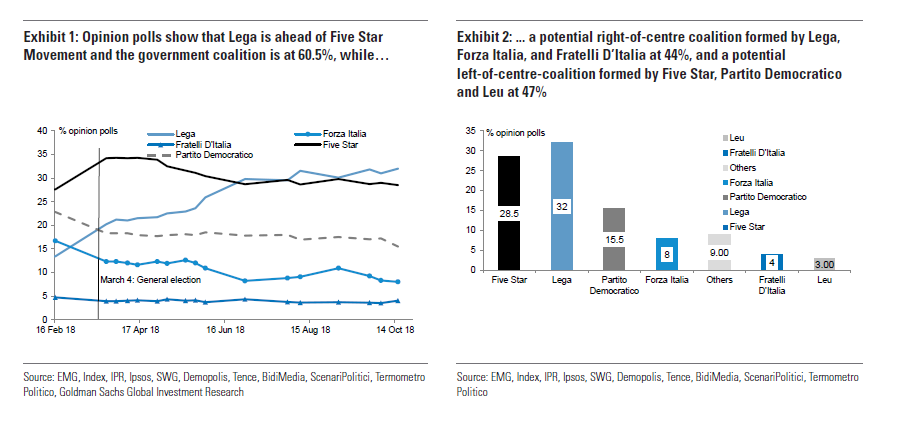

Al momento la coalizione di maggioranza ha il supporto di circa il 60% dell’elettorato, sottolinea Goldman Sachs, secondo cui “l’attuale governo sopravviverà almeno fino alle prossime elezioni europee di maggio e non tornerà indietro dai suoi propositi in materia di politiche di bilancio almeno fino a quel momento”.

LE RAGIONI DELLA PROSSIMA CADUTA SECONDO GLI ANALISTI DI GOLDMAN SACHS

Tale valutazione si basa sul fatto che i “partiti di governo puntano a massimizzare il voto alle europee e potrebbero cercare di realizzare alleanze con altri partiti europei che condividano una visione simile, con l’obiettivo di cambiare la rete istituzionale nella direzione da loro preferita (allentamento delle regole fiscali, cambio del mandato della Bce, stretta sulle politiche riguardanti l’immigrazione)”.

CHE COSA PREFERISCE LA BANCA D’AFFARI AMERICANA

Infine, il “voto politico” della banca d’affari Usa: “Un nuovo governo, o di centrodestra o di centrosinistra, perseguirebbe una politica fiscale complessivamente meno espansiva e porterebbe probabilmente a un miglioramento nei mercati finanziari e a una ripresa delle attività. Ma, da una prospettiva di medio termine, è improbabile che un governo del genere sia in grado di migliorare la qualità delle istituzioni, faccia le riforme necessarie per aumentare la produttività e la crescita potenziale e crei quel circolo virtuoso di lungo termine necessario per un declino del rapporto debito/Pil. Quindi, molto probabilmente, una risoluzione della crisi attuale dell’Italia permetterebbe al Paese di cavarsela fino alla prossima crisi”, conclude Goldman Sachs.

LE SCIAGURE PER L’ITALIA SECONDO L’ECONOMISTA DI GS

Non è una novità assoluta l’impostazione della banca d’affari americana. Ecco quello quello che ha scritto nei giorni scorsi l’economista di Goldman Sachs Silvia Ardagna: “La situazione dei mercati [italiani] potrebbe dover peggiorare prima di poter migliorare”.

Perché? “Il ragionamento di Ardagna è piuttosto semplice – si legge su Business Insider – Il governo italiano non vuole fare un passo indietro rispetto all’imposizione del suo nuovo bilancio, che l’ha portato allo scontro con Bruxelles”. Prosegue l’economista dell’agenzia di rating: “I soggetti che partecipano ai mercati finanziari sono consapevoli che esiste un valore nell’attribuzione del prezzo giusto non solo al ‘finale di partita’, ma anche alla strada percorsa per giungere a quel ‘finale di partita’ e ai rischi che comporta” ha scritto Ardagna ai clienti in una nota nella prima metà di ottobre, esprimendo un punto che ha poi reiterato lunedì scorso, chiosa Business Insider.

L’AUSPICATO CAMBIAMENTO POLITICO IN ITALIA

Il pensiero stile S&P’s si chiarisce ulteriormente con un altro brano del report di Adragna: “Il nostro punto di vista è che le tensioni sui mercati dovrebbero intensificarsi per esercitare una pressione sufficiente sul sistema politico italiano per determinare un cambiamento della linea politica e della retorica a essa associata. Su tale base — e anche se l’Italia alla fine continuerà a far parte dell’eurozona — la situazione dei mercati potrebbe dover peggiorare prima di poter migliorare”.

Tutto chiaro.

**************DI SEGUITO IL TESTO INTEGRALE DEL REPORT GOLDMAN SACHS**********************

On Friday evening (19 October), Moody’s downgraded the Government n of Italy’s local and foreign-currency issues to Baa3, the lowest investment grade and introduced a stable rating outlook. The prior rating was Baa2 on negative watch.

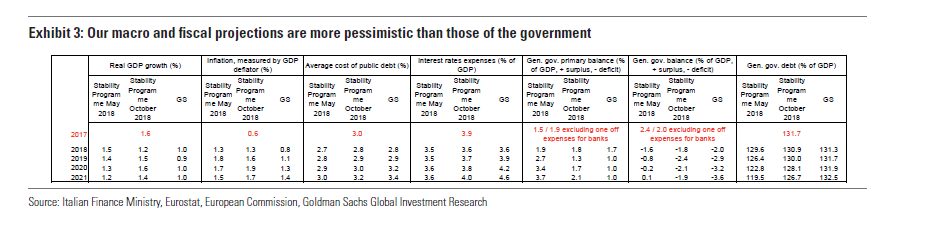

This downgrade was broadly in line with market expectations. Our own macro and fiscal projections for Italy are more pessimistic than those of either the Italian government or Moody’s. We anticipate that the new measures included in the recent budget plan will lead to a deterioration in the fiscal outlook beyond that which is incorporated in the government’s or Moody’s forecasts.

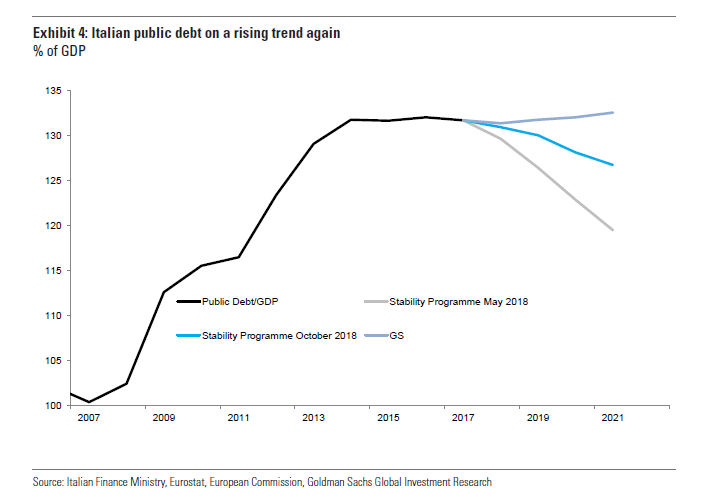

Moreover, we forecast both lower nominal GDP growth and higher interest rate expenses than the government, leading us to expect that the public debt-to-GDP ratio will rise in the coming years.

In its ratings assessment, Moody’s treated the pension changes permitting earlier retirement as a one-off change to the current law, which allows workers to retire earlier only in 2019. In our view, there is considerable uncertainty that the Italian Parliament will pass such a change to the pension system only for one year. We think the cost of the pension changes over the period 2019-2021 could therefore be higher than projected by Moody’s and the government. Under this scenario, the medium-term fiscal outlook in Italy would be worse than Moody’s current assessment, potentially justifying future further downgrades of the Italian sovereign.

On the back of maintaining a sovereign investment grade rating from Moody’s (as well as some more conciliatory comments from Brussels), Italian assets could enjoy a period of temporary relief. That said, we continue to think that the market situation may need to get worse before it gets better, in order to exert the pressure required to trigger a change in the course of and rhetoric surrounding fiscal policy.

Italy — Some temporary relief

Last Friday (19 October), Moody’s downgraded the Government of Italy’s local and foreign-currency issues to Baa3, the lowest investment grade and introduced a stable rating outlook. The prior rating was Baa2 on negative watch.

This downgrade was broadly in line with market expectations. It has removed the risk of a worse outcome – either (i) the maintenance of the negative outlook after aone notch downgrade or (ii) a two notch downgrade, placing Italy below investment grade. Having avoided the worse outcome, we think Italian assets could enjoy a period of temporary relief, with BTP yields stabilizing close to the levels observed over the past two weeks.

Yet we continue to think that more market pressure will be required to trigger a changein the course of and rhetoric surrounding fiscal and economic policies that are needed tobring Italian public debt back onto a downward trajectory. Such a policy change is not insight yet.

Over the past few days, the two governing populist parties have publicly disagreed overthe fiscal amnesty decree, but now appear to have found a compromise over the details. Latest opinion polls continue to show Lega leading: the adoption of a budget plan skewed more toward spending increases than tax cuts (and thus to Five Star rather than Lega priorities) has not shifted voting intentions (Exhibits 1 and 2).

We identify a number of specific upcoming events with potentially important implications for Italian asset prices: (i) the Italian government’s response to the European Commission’s letter on the draft budget law (due on Monday 22 October); (ii) the European Commission’s formal assessment of the 2019 budget plan (likely to come by month-end); (iii) S&P’s credit rating decision (on October 26); and (iv) the formal submission of decrees implementing the measures included in the budget plan to the Italian Parliament.

The rationale underlying Moody’s decision and the key risks ahead

The rationale underlying Moody’s decision to downgrade Italian debt to the lowest investment grade level (with a stable outlook) is:

the deterioration of the fiscal outlook owing to the higher n government deficits, which – on the basis of Moody’s projections – will keep public debt stable at around 130% of GDP (rather than placing it on a declining path, as previously expected); and the lack of a “coherent agenda of reforms that will address Italy’s n sub-par growth performance on a sustained basis“. Moody’s forecasts that Italian real GDP growth will fall back to its trend rate of around 1%pa, after some limited and temporary boost stemming from the fiscal stimulus embodied in the budget plan.

Crucially, while recognising that the changes could become permanent, in its ratingassessment Moody’s treated the proposed pension changes that permit retirement at an earlier age as a one-off change to the current law, which allows workers to retire earlier only in 2019. (See below for more on this.)

Moody’s adoption of a stable outlook reflects its broadly balanced assessment of risk atthe Baa3 rating level. While the weakening fiscal outlook points to downside risks, Moody’s also points to a number of Italian strengths: (i) a very large and diversified economy, (ii) a solid external position, with substantial current account surpluses and a near balanced international investment position, and (iii) the high level of Italian household wealth.

Looking ahead, Moody’s signals that a positive rating action is currently unlikely. An upgrade would require the Italian government to implement policies that remove the key rationale for the downgrade, i.e. that improve the fiscal outlook and, via structural reform, raise productivity growth.

In Moody’s assessment, the following reasons could lead to a worse rating: (i) a further deterioration of the economic and fiscal outlook, (ii) the government’s unwillingness to take, if needed, corrective fiscal measures to keep the public debt on a stable trajectory, (iii) a sustained and material increase in the cost of servicing the Italian public debt, implying an increased risk of the government losing market access, and (iv) a material rise in the risk of Italy exiting the Euro area.

The devil of the 2019 budget plan is in the details Our macro and fiscal projections are more pessimistic than those of the government (Exhibits 3 and 4). We anticipate that the new measures included in the recent budget plan will lead to a deterioration in the fiscal outlook beyond that which is incorporated in government forecasts. We also think that the savings and revenue raising measures in other parts of the budget projected by the government will be difficult to achieve.

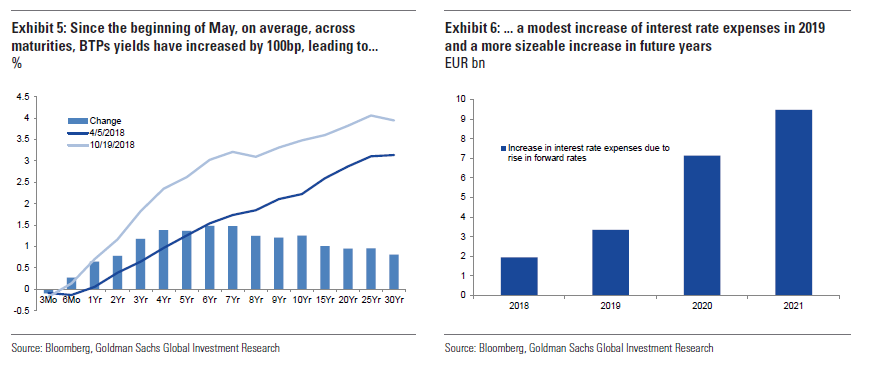

Moreover, we forecast both lower nominal GDP growth and higher interest rate expenses than the government (Exhibits 5 and 6), leading us to expect that the public debt-to-GDP ratio will rise in the coming years.

The 2019 budget plan does not provide detail on specific fiscal measures. In particular, the specifics of pension changes and the minimum universal income scheme have yet to be published. The details should become available in coming weeks.

On the basis of only the currently available information, we reach a different and less favourable conclusion to Moody’s on the likely impact of pension and universal income measures on Italian fiscal dynamics over the medium term.

The cost of the pension reform and…

In its rating’s assessment, Moody’s treated the pension changes permitting earlier retirement as a one-off change to the current law, which allows workers to retire earlier only in 2019. This follows on from the government’s published projection of a constant cost of the pension changes over time (approximately EUR 7bn -0.3% of GDP- per year in 2019-2021) in its 2019 budget documents.

We disagree with such an assessment. In our view, there is considerable uncertainty that the Italian Parliament will pass such a change to the pension system only for one year. We think the cost of the pension changes over the period 2019-2021 could therefore be higher than projected by the government (and assumed by Moody’s).

Under this scenario, the medium-term fiscal outlook in Italy would be worse than Moody’s current assessment potentially justifying future further downgrades of the Italian sovereign: the cost of the pension reform would increase over time, and lead to a cumulative increase of public debt. (We note that based on estimates of INPS – the National Institute of Pensions – and reported by Corriere della Sera, the cost of the pension changes will be approximately EUR 7bn in 2019, EUR 11.5bn in 2020, EUR 17bn in 2021; the resulting increase of public debt will be approximately 10% of GDP over ten years.)

…the cost of the minimum universal income scheme could be significantly higher than projected in years beyond 2019

The cost of the minimum universal income and pension scheme is projected at approximately EUR 10bn per year. The measure aims to guarantee to each citizen an income or pension of EUR 780 per month, the level of income estimated by the OECD as the threshold of the poverty line. The cost of this measure could also increase over time significantly given:

(1) The OECD could revise the threshold of the poverty line’s income.

(2) More importantly, this measure could lead to a decline in the labour force participation and increase the number of citizens entitled to receive the transfer. According to local media and statements from politicians, the requirements to receive the minimum income scheme would be: (i) participation in job training, (ii) work in public or social services, (iii) accepting the third job offer received (provided it doesn’t force workers to move too far from their home). Under these constraints, it is possible that workers whose salaries are at or below EUR 780 per month could quit their job and prefer to receive the minimum universal income.

(3) The government says that in 2019 the minimum income will be delivered starting from Q2. In our view, it is unlikely that the cost of the programme in 2020 and 2021, for a twelve month period, will be the same of the cost in 2019 when transfers are paid for nine months.

Weaker economic outlook

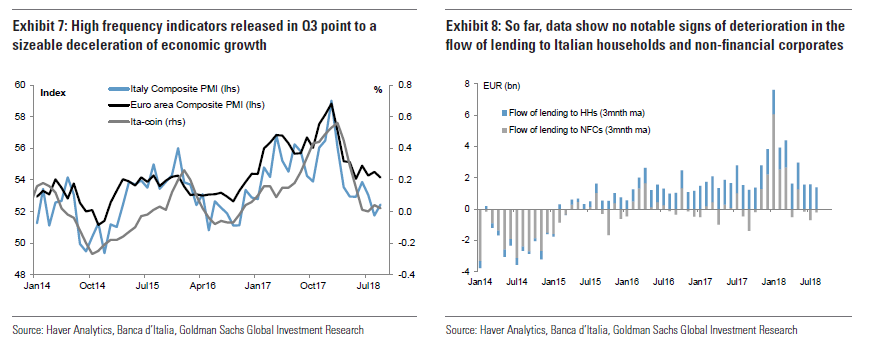

High frequency indicators released in Q3 point to a sizeable deceleration of economic growth. We forecast real GDP growth in Q3 at 0.1%qoq and think the risks to our forecast are skewed to the downside. The Bank of Italy also expects Q3 real GDP growth close to zero. The first release of Q3 GDP is on 30 October. We forecast real GDP growth of 0.9%yoy in 2019 and 1%yoy in 2020.

Based on our analysis of the fiscal multipliers, we are sceptical that the fiscal easing proposed by the government (as embodied in the changes to the size and composition of the budget highlighted above) will stimulate real GDP growth to rates above our forecast.

In line with the economic literature, we find that (i) tax multipliers tend to be much larger than government spending multipliers in countries with median public debt-to-GDP ratios and (ii) that both tax and spending multipliers are much smaller in high debt countries such as Italy (see European Economics Analyst: An Italian fiscal expansion — Part II: Not so growth supportive, may halt decline in public debt-to-GDP ratio).

In some empirical models, we also find that the fiscal multiplier of public current spending (i.e. the bulk of the 2019 fiscal expansion) is negative, which means that an increase in current spending leads to a decline in real GDP. This is because the increase in interest rates and the widening of spreads that occur on the back of a fiscal expansion in high debt countries leads to an increase in the banks’ cost of funding, which is passed onto consumers and firms. This crowds out private consumption and private investment.

So far, data on bank deposits, loans volumes and interest rates charged on consumers and firms’ loans do not show notable signs of deterioration in credit supply conditions.

But the data available so far cover the period until July-August. More recent data should provide us with direct evidence on the effect of the increase in interest rates and banks funding costs on credit supply and the real economy.

The experience of the financial crisis also offers some guidance. Since the beginning of May, the 5-year CDS of major Italian banks has increased by approximately 175%, not so much lower than the increase in 2011, of approximately 210%. Balduzzi et al. estimate the impact of the credit crunch (measured via the increase in banks’ CDS) on investment and employment of Italian firms of different sizes and ages during the period 2007-2013. On that basis, the increase in bank CDS rates seen thus far in 2018 could lead to a decrease in capital accumulation of about 3.5% and of employment of about 2% over a one year period. These effects are sizeable: consider that in 2017 private fixed investment increased by 4.3% in real terms and private employment by 1%. Only about half of this potential slowdown in private fixed investment is incorporated in our current economic forecasts covering the period 2019-2021, pointing to a significant downside risk to our economic outlook.

Finally, the decrease in government bond prices also has negative effects on household wealth which can lower consumer and business confidence. The fall in confidence indicators that have occurred since May offer some preliminary indications of a potential crowding-out of private sector demand.